Attrition Bias | Examples, Explanation, Prevention

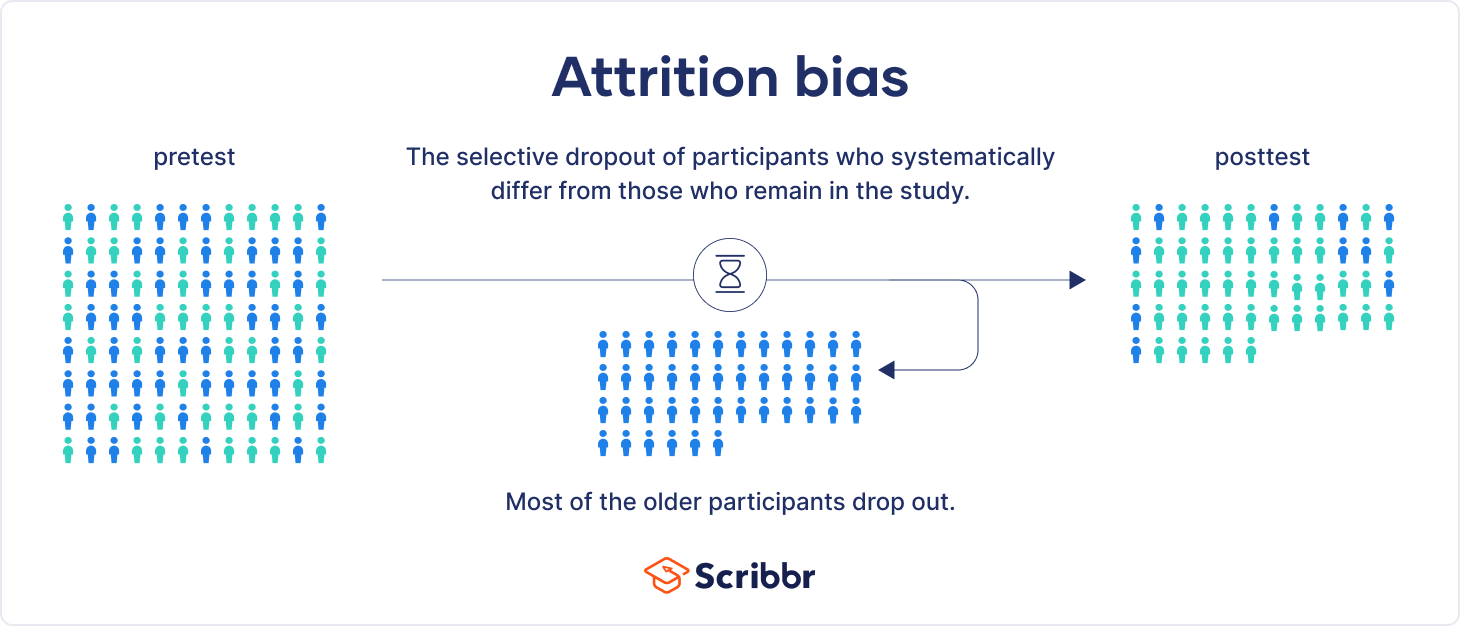

Attrition bias is the selective dropout of some participants who systematically differ from those who remain in the study. Almost all longitudinal studies will have some dropout, but the type and scale of the dropout can cause problems.

Attrition is participant dropout over time in research studies. It’s also called subject mortality, but it doesn’t always refer to participants dying!

Attrition bias is especially problematic in randomised controlled trials for medical research.

What is attrition?

In experimental research, you manipulate an independent variable to test its effects on a dependent variable. You can often combine longitudinal and experimental designs to repeatedly observe within-subject changes in participants over time.

You provide a treatment group with short drug education sessions over a two-month period, while a control group attends sessions on an unrelated topic.

Most of the time, when there are multiple data collection points (waves), not all of your participants are included in the final sample.

More and more participants drop out at each wave after the pretest survey, leading to a smaller sample at each point in time. This is called attrition.

Reasons for attrition

Participants can drop out for any reason at all. For example, they may not return after a bad experience, or they may not have the time, motivation, or resources to continue taking part in your study.

In clinical studies, participants may also leave because of unwanted side effects, dissatisfaction with treatments, or death from other causes.

Alternatively, you may also need to exclude some participants after a study begins for not following study protocols, for identifying the study aim, or for failing to meet inclusion criteria.

Types of attrition

Attrition can be random or systematic. When attrition is systematic, it’s called attrition bias.

Random attrition

Random attrition means that participants who stay are comparable to the participants who leave. It’s a type of random error.

You find no statistically significant differences between those who leave and those who stay while checking your study data.

Note that this type of attrition can still be harmful in large numbers because it reduces your statistical power. Without a sufficiently large sample, you may not be able to detect an effect if there is one in the population.

Attrition bias

Attrition bias is a systematic error: participants who leave differ in specific ways from those who remain.

You can have attrition bias even if only a small number of participants leave your study. What matters is whether there’s a systematic difference between those who leave and those who stay.

According to the data, participants who leave consume significantly more alcohol than participants who stay. This means your study has attrition bias.

Why attrition bias matters

Some attrition is normal and to be expected in research. But the type of attrition is important, because systematic research bias can distort your findings.

Attrition bias can lead to inaccurate results, because it can affect internal and/or external validity.

Internal validity

Attrition bias is a threat to internal validity. In experiments, differential rates of attrition between treatment and control groups can skew results.

This bias can affect the relationship between your independent and dependent variables. It can make variables appear to be correlated when they are not, or vice versa.

For the participants who stay, the treatment is more successful than the control protocol in encouraging responsible alcohol use.

But it’s hard to form a conclusion, because you don’t know what the outcomes were for the participants who left the treatment group.

Without complete sample data, you may not be able to form a valid conclusion about your population.

External validity

Attrition bias can skew your sample so that your final sample is significantly different from your original sample. Your sample is biased because some groups from your population are underrepresented.

With a biased final sample, you may not be able to generalise your findings to the original population that you sampled from, so your external validity is compromised.

Your final sample is skewed towards college students who consume low-to-moderate amounts of alcohol.

Your findings aren’t applicable to all college students, because your sample underrepresents those who drink large amounts of alcohol.

Ways to prevent attrition

It’s easier to prevent attrition than to account for it later in your analysis. Applying some of these measures can help you reduce participant dropout by making it easy and appealing for participants to stay.

- Provide compensation (e.g., cash or gift cards) for attending every session

- Minimise the number of follow-ups as much as possible

- Make all follow-ups brief, flexible, and convenient for participants

- Send routine reminders to schedule follow-ups

- Recruit more participants than you need for your sample (oversample)

- Maintain detailed contact information so you can get in touch with participants even if they move

Detecting attrition bias

Despite taking preventive measures, you may still have attrition in your research. You can detect attrition bias by comparing participants who stay with participants who leave your study.

Use your baseline data to compare participants on all variables in your study. This includes demographic variables – such as gender, ethnicity, age, and socioeconomic status – and all variables of interest.

You’ll often note significant differences between these groups on one or more variables if there is bias.

You collected data on these variables:

- Age

- Gender

- Ethnicity

- Socioeconomic status

- Alcohol use frequency

- Alcohol use amount

- Treatment or control group assignment

Using a logistic regression analysis, you divide up the participants into two groups, based on whether they stay or leave, and enter the variables as coefficients to test for differences.

The coefficients for the alcohol use frequency and amount variables are significant, indicating attrition bias based on those variables. The participants who remain differ from those who drop out in terms of their alcohol use amount and frequency.

If you don’t find significant results, you may still have a hidden attrition bias that isn’t easily found in your data.

Try to follow up with participants to understand their reasons for leaving and check for any common causes for dropout if you are able to contact them.

Even if you can’t identify attrition bias, a follow-up survey of participants who drop out may help you design future studies that prevent attrition bias.

How to account for attrition bias

It’s best to try to account for attrition bias in your study for valid results. If you have a small amount of bias, you can select a statistical method to try to make up for it.

These methods help you recreate as much of the missing data as possible, without sacrificing accuracy.

Multiple imputation

Multiple imputation involves using simulations to replace the missing data with likely values. You insert multiple possible values in place of each missing value, creating many complete datasets.

These values, called multiple imputations, are generated using a simulation model over and over again to account for variability and uncertainty. You analyse all of your complete datasets and combine the results to get to estimates of your mean, standard deviation, or other parameters.

Sample weights

You can use sample weighting to make up for the uneven balance of participants in your sample.

You adjust your data so that the overall makeup of the sample reflects that of the population. Data from participants similar to those who left the study are overweighted to make up for the attrition bias.

Low and moderate alcohol drinkers each get an equal weighting of 1, which means their data are multiplied by 1. Meanwhile, heavy drinkers get assigned a higher weighting of 1.5, so the date of each of these participants are overweighted in the complete dataset.

Other types of research bias

Frequently asked questions about attrition bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, March 04). Attrition Bias | Examples, Explanation, Prevention. Scribbr. Retrieved 18 April 2025, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/bias-in-research/attrition-bias-explained/