What Is Social Desirability Bias? | Definition & Examples

Social desirability bias occurs when respondents give answers to questions that they believe will make them look good to others, concealing their true opinions or experiences. This type of research bias often affects studies that focus on sensitive or personal topics, such as politics, drug use, or sexual behaviour.

Social desirability bias is a type of response bias. Here, study participants have a tendency to answer questions in such a way as to present themselves in socially acceptable terms, or in an attempt to gain the approval of others.

It is especially likely to occur in self-report questionnaires, but it can also affect the validity of any type of behavioural research, particularly if the participants know they’re being observed.

The risk of researchers or respondents influencing (biasing) a study and its results, whether consciously or unconsciously, is inherent to conducting human-centred research. However, there are ways to detect and reduce bias in your research design if you know what to look for.

Due to this, participants may downplay how often they visit a casino or use cocaine. In other words, they may give answers they consider to be socially desirable in order to project a favourable image of themselves, or to avoid being perceived negatively.

Table of contents

- Why does social desirability bias occur?

- Types of social desirability bias

- Why social desirability bias matters

- Social desirability bias examples

- When does social desirability bias occur?

- How to reduce social desirability bias in your research design

- How to detect social desirability bias

- Other types of research bias

- Frequently asked questions about social desirability bias

Why does social desirability bias occur?

While social desirability bias may be caused by the nature or setting of the experiment, it’s important to remember that the desire to act in a culturally appropriate and acceptable manner is deeply rooted in human nature. For this reason, the mere presence of a researcher or other participants may trigger some level of socially desirable responding.

However, each individual respondent may also have their own reasons to want to be perceived a certain way (e.g., seeking approval or desiring praise), as well as expectations regarding how their behaviour will be evaluated by others.

Types of social desirability bias

In general, there are two types of social desirability bias:

- Self-deceptive enhancement (self-deception)

- Impression management (other-deception)

This distinction is important because it accounts for both situational factors (related to a situation) and personal factors (related to personality traits) that can result in socially desirable behaviour. While situational determinants can be influenced by the researcher, personal determinants are less easily controlled for. These can usually only be detected after the fact.

Self-deceptive enhancement

Self-deceptive enhancement occurs when the respondent believes something to be true when it is not. In this case, the respondent is neither aware of portraying themselves positively nor consciously trying to, but does so anyway.

Here, the interviewee has formed an expectation about what the researcher or broader society will consider acceptable behaviour, and wants to show that they meet this standard. In this case, recycling is considered ‘good’ behaviour. As the interviewee considers themselves a good person, they may believe that they recycle more than they do.

Impression management

On the other hand, when people engage in impression management, they are not only aware of their overconfident self-appraisal, but are actually intentionally seeking to keep up with social or group norms in order to avoid negative evaluation or judgment.

Here, a member of a youth gang may admit to many more violations than they committed in order to appear tough and world-wizened. Conversely, a teacher may admit to fewer violations in order to appear compliant.

Why social desirability bias matters

Social desirability bias is one of the most common sources of bias. It leads to over-reporting of socially desirable behaviours or attitudes, and under-reporting of socially undesirable behaviours or attitudes. As a result, reported answers will differ from true answers.

Socially desirable responses can bias results in three main ways:

- Social desirability can cause a spurious correlation to occur between variables, making them appear to have a causal relationship when they do not.

- Social desirability can hide relationships between variables by acting as a suppressor variable.

- Social desirability can act as a moderator variable, even though it may or may not be uncorrelated to either the independent or dependent variables.

Social desirability bias examples

You need to consider social desirability bias when deciding what research design would work best for you.

You expect that if you ask the children themselves, they are unlikely to admit to engaging in behaviours like hitting others. Even from a young age, they are aware that this is not socially acceptable. Similarly, if the children are aware that their behaviour is being observed, they will also probably behave differently.

Taking this into account, you determine that observation is still the best method, but only so long as children don’t notice your presence (called covert observation). You plan to stand behind a tree at a school playground, jotting down any instances of hitting, kicking, or other aggressive behaviour.

If you interviewed them individually or in groups, chances are that your presence or other participants’ presence would trigger some level of socially desirable responding. If students know most of their peers don’t eat meat, some may feel embarrassed to admit to eating meat, thus reporting that they eat less than they actually do.

You decide that an online survey guaranteeing respondents’ anonymity is a more suitable approach.

When does social desirability bias occur?

Unfortunately, it’s often not possible to fully prevent or remove social desirability bias from your research. However, it is important to identify and control for the influence of this bias, starting with your research design. The first step here is to recognise and anticipate conditions where bias is particularly likely to occur.

These can include:

- Research designs that incorporate self-report measures

- Studies involving personal or sensitive topics

- Situations in which subject anonymity is compromised or not guaranteed

- Instances when subjects anticipate that their responses will result in judgment from others

- Situations in which participants belong to similar social groups to the interviewer

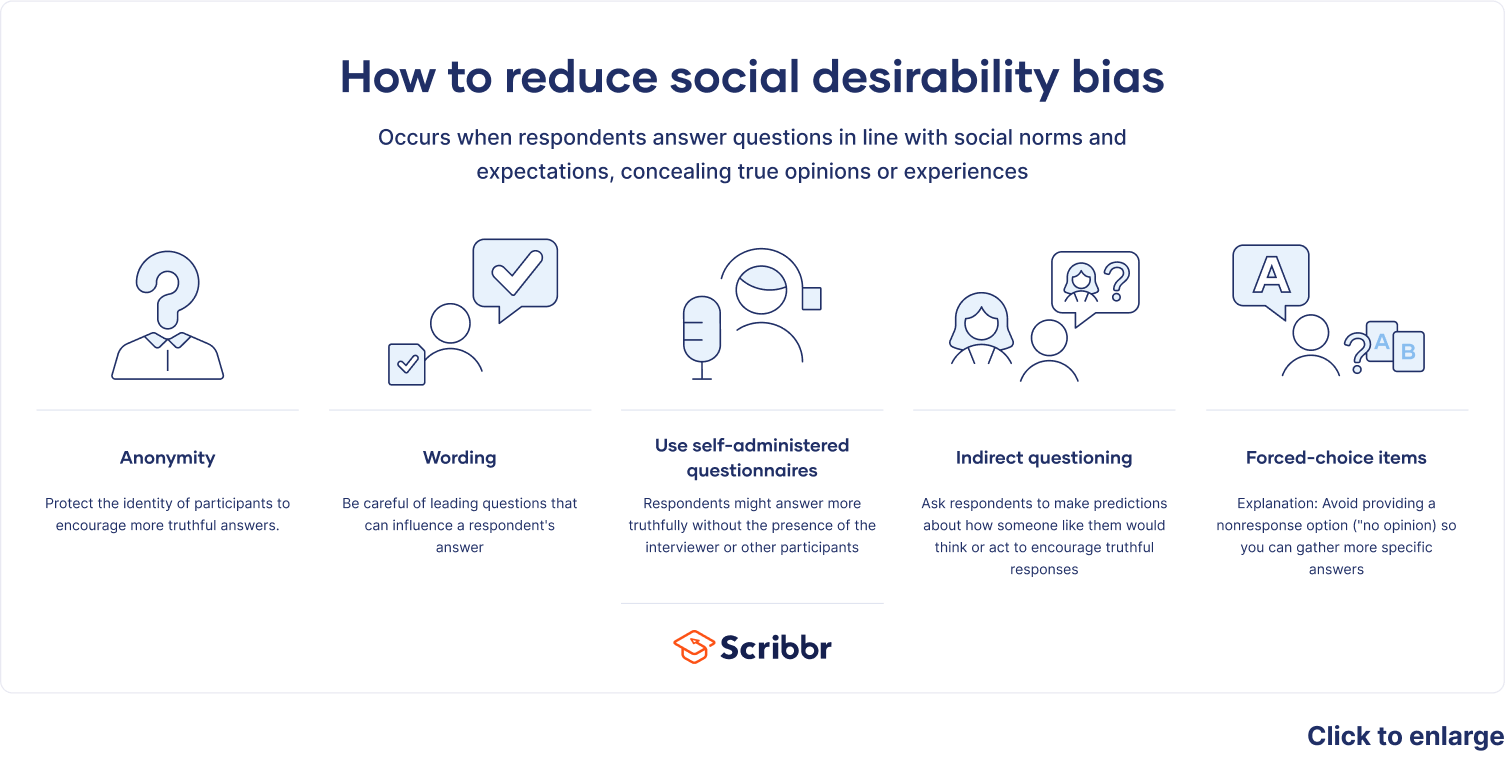

How to reduce social desirability bias in your research design

There are a few strategies that you can use to help you reduce social desirability bias in your research design.

Anonymity

When asking about sensitive topics such as drug use or breaking the law, it’s important to reassure the study participants that their identities will be protected. If your results are appropriately anonymised, you may receive more truthful answers.

Wording

Be wary of leading questions that can influence a respondent’s answer. The phrasing of a questionnaire item can trigger a socially desirable response, even when the respondent doesn’t have the tendency to respond in such a fashion.

While this may seem like a well-formed question, notice that the wording already assumes that this diagnosis method is, by definition, challenging. Even if some respondents may not think so, they may feel like they need to imagine challenges in order to answer the question the way they perceive the interviewer wants them to.

A better option could be ‘What were your experiences learning how to diagnose patients using a distance learning method?’

Self-administered questionnaires

Giving respondents the opportunity to fill out a questionnaire at a time and place where they are undisturbed by others may lead to more truthful answers. As mentioned above, the presence of the interviewer or other participants may give them conscious or unconscious cues to answer in a socially desirable manner.

Online surveys or questionnaires in particular are a great way to minimise socially desirable responses. However, note that the absence of an interviewer here limits the usefulness of self-administered surveys to cases where the questions are not complex. You are also limited to questions that are mainly closed-ended.

You suspect that asking students to complete the survey in class may trigger some of them to hide risky sexual behaviour, fearing that others will peek at their answers or ask them about it after class. Since this is a sensitive topic, you decide to send them the survey online and instruct them to fill it in at home.

Indirect questioning

Indirect questioning asks respondents to answer a set of structured questions from the perspective of another person or group. A typical indirect question asks respondents to make predictions about how someone like them would think or act in a particular situation.

The underlying idea here is that indirect questions can reduce social desirability bias. As respondents feel that they are giving information about situations based on objective facts rather than their own opinions, they project their attitudes into the response situation.

- A direct question would be ‘It’s very important/somewhat important/not important to me that others approve of my purchase of product X.’

- An indirect question would be ‘It’s very important/somewhat important/not important to the typical student that others approve of their purchase of product X.’

Many people are reluctant to admit that what others think plays a role in their purchase decisions. The tendency to present oneself in the best possible light can lead respondents to underreport the importance of social approval if asked about it directly. However, asking indirect questions may lead respondents to project their real attitudes.

Forced-choice items

A forced-choice question requires the respondent to provide a specific answer, without giving a ‘nonresponse’ option such as ‘no opinion’, ‘don’t know’, ‘not sure’, or ‘not applicable’. Depending on the specific forced-choice design, respondents are asked either to:

- Choose an item within each block that is more descriptive of them

- Choose the most descriptive and the least descriptive item

- Provide a full ranking of items within each forced-choice block

What you could do instead is ask people to rank several items that possess an equal degree of social desirability. Here’s an example:

Please rank the following possible work situations according to how much they appeal to you.

__ Assignment to individual tasks that allow you 100% control over your performance.

__ Assignment to tasks that require a small team where others may influence your performance, but that would provide more social interaction.

__ Assignment to tasks that require cooperation and coordination with numerous other employees, influencing your ability to perform but maximising social interaction.

How to detect social desirability bias

You can detect and measure social desirability bias using two methods:

Social desirability scales

A number of social desirability (SD) scales have been developed in an effort to detect and measure socially desirable responses in data collection. These include the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale, the Martin-Larsen Approval Motivation Scale, the Self-Deception Questionnaire (SDQ), and others.

These scales involve a number of true or false statements concerning personal attitudes and traits. They describe socially desirable but statistically unlikely behaviours, such as ‘Before voting, I thoroughly investigate the qualifications of all candidates.’ Based on their answers, each respondent is assigned a social desirability score. Individuals who agree with these statements will have a higher score.

After checking for correlation with social desirability scores, you can then use three tactics:

- Reject the data from subjects you deem to have scored too highly

- Correct data from high scorers (for example, by using data from a control group)

- Note or register the impact of social desirability bias in your paper

Rating of item desirability

Item desirability is measured by asking subjects to rate an item (e.g., a question or a statement) on a desirability scale. For example, if ‘being happy’ is an item, subjects are asked to indicate how desirable being happy is to them. This rating is added to each of the questions in the survey.

Keep in mind that adding a rating to each question can be an inconvenient method if there are many questions, as the length of the questionnaire is effectively doubled.

Alternatively, using pre-existing content scales that have been examined for evidence of social desirability bias may aid in reducing the likelihood of encountering a response bias.

Other types of research bias

Frequently asked questions about social desirability bias

- What is the definition of response bias?

-

Response bias refers to conditions or factors that take place during the process of responding to surveys, affecting the responses. One type of response bias is social desirability bias.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Nikolopoulou, K. (2023, March 24). What Is Social Desirability Bias? | Definition & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 23 November 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/bias-in-research/what-is-social-desirability-bias/