Slippery Slope Fallacy | Definition & Examples

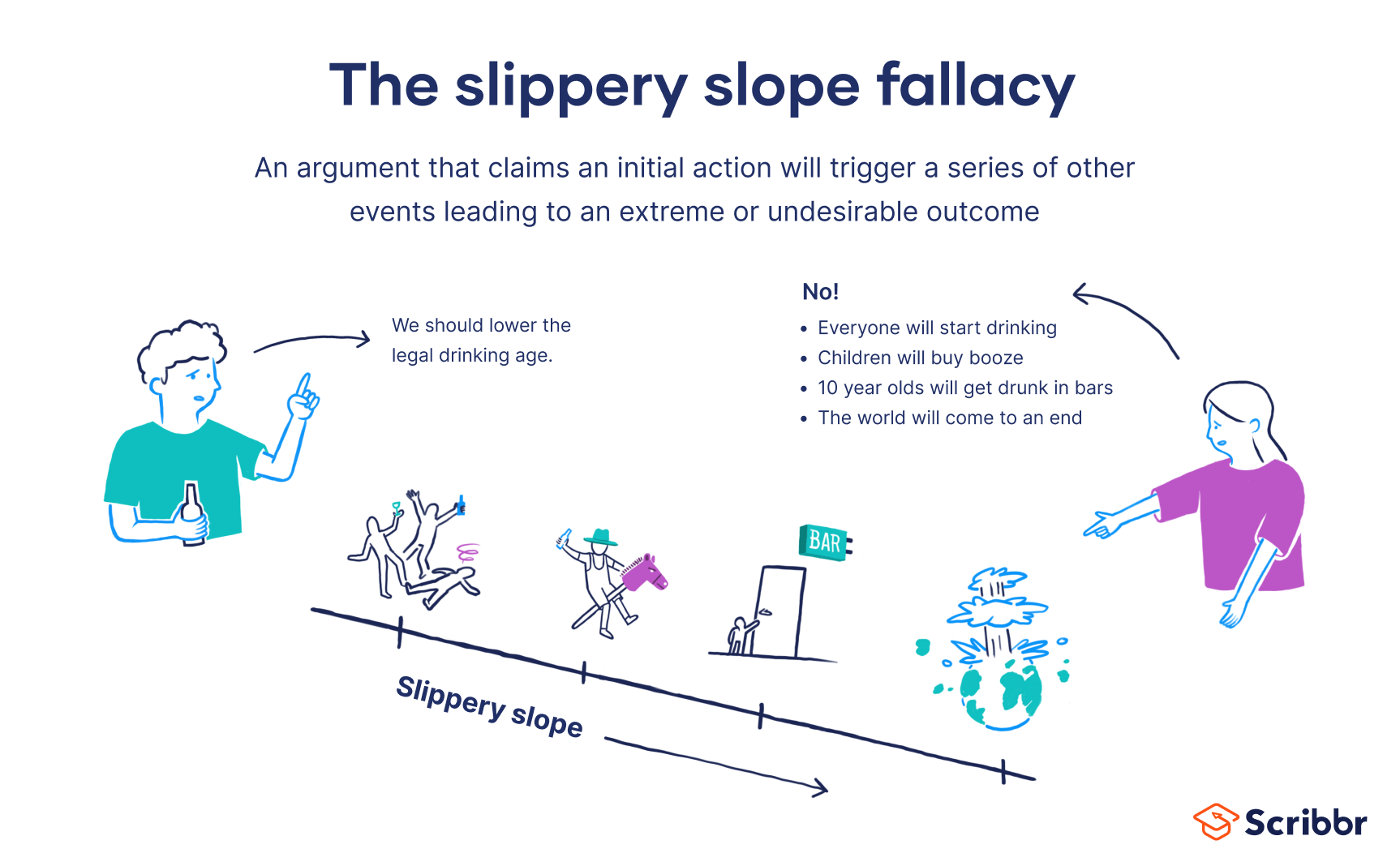

The slippery slope fallacy is an argument that claims an initial event or action will trigger a series of other events and lead to an extreme or undesirable outcome. The slippery slope fallacy anticipates this chain of events without offering any evidence to substantiate the claim.

Person B: “No, if we do that, we’ll have ten-year-olds getting drunk in bars!”

As a result, the slippery slope fallacy can be misleading both in our own internal reasoning process and in public debates.

What is the slippery slope fallacy?

Slippery slope fallacy occurs when a person asserts that a relatively small step will lead to a chain of events that result in a drastic change or a negative outcome. This assertion is called a slippery slope argument.

This is problematic as the person assumes a cause-and-effect relationship between two or more events or outcomes without knowing for sure how things will pan out. This progression of actions or events is presented as inevitable and impossible to stop (much like the way one step on a slippery incline will cause a person to fall and slide all the way to the bottom). However, little or no evidence is presented to back up the claim.

The slippery slope fallacy is a logical fallacy or reasoning error. More specifically, it is an informal fallacy where the error lies in the content of the argument rather than its format (formal fallacy). Therefore, not every slippery slope argument is flawed. When there is evidence that the consequences of the initial action are highly likely to occur, then the slippery slope argument is not fallacious.

“If I don’t pass tomorrow’s exam, I will not get the GPA I need to go to a good college, and then I won’t be able to find a job and earn a living. If I don’t pass the exam, my life is ruined!”

This is a fallacy because there is only an assumed connection between passing an exam and finding a good job. It’s an extreme conclusion that doesn’t logically follow.

Non-fallacious

“If I don’t pass tomorrow’s exam, this might affect my GPA, which in turn might impact my chances of going to a good college.”

Here, the slippery slope (A leads to B, B leads to C, etc.) is in the form of a logical extrapolation to a possible outcome. Therefore, it is not fallacious.

Why is the slippery slope fallacy used?

People use the slippery slope fallacy as a rhetorical device to instill fear or other negative emotions in their audience. It is often used to argue against a specific decision by adopting its (hypothetical) extreme consequences as if they were a certainty. This is a form of fearmongering (or appeal to emotion) that can be misleading because there is no proof that these extreme consequences will in fact materialise.

However, slippery slope arguments are not always negative or oppositional. It is possible to use a slippery slope argument to argue in favor of a proposition. In this case, they appeal to positive emotions like optimism. For example, “If we give everyone universal basic income, people will take the risk to set up their own businesses and ultimately turn into successful entrepreneurs.”

What are different types of slippery slope fallacy?

Different philosophers have classified slippery slope arguments in different ways. In general, there are three main types of slippery slope fallacies, depending on the type of erroneous argument at their core.

Causal slippery slope arguments

Causal slippery slope arguments suggest that a minor initial action or event will inevitably lead to a series of others, with each event or action being the cause of the next in the sequence.

Precedential slippery slope arguments

Precedential slippery slope arguments claim that if we treat a minor case or issue in a specific way today, we will have to treat any major case or issue that may arise in the future the same way.

Conceptual slippery slope arguments

Conceptual slippery slope arguments assume that because we cannot draw a distinction between adjacent stages, we cannot draw a distinction between any stages at all.

Regardless of their form, slippery slope arguments are presented as a series of conditional propositions, such as “if A, then B” and “if C, then D”, the idea being that through a series of intermediate steps A implies D. Usually they start with a moderate claim and gradually escalate to an extreme end point with no possibility to stop in between.

Slippery slope fallacy examples

Advertisers resort to slippery slope fallacies when trying to sell us a number of everyday products.

Slippery slope fallacy examples in advertising

Toothpaste commercials often rely on slippery slope arguments in the form of “if you don’t buy this toothpaste, you will get cavities and lose all your teeth.”

By presenting the worst-case scenario as the inevitable consequence of not buying that certain product, advertisers try to bypass logic and play on our fears. This is of course an irrational proposition, since it ignores all other factors that may affect our dental health.

Slippery slope fallacy examples in media

Interviews and debates on controversial topics are rife with slippery slope fallacies.

Using slippery slope arguments is often intentional so that the speaker avoids engaging with the issue at hand and instead shifts attention to its extreme hypothetical consequences. By equating the issue with its (hypothetical) negative consequences, the speaker tries to “win” the debate.

Other interesting articles

If you want to know more about fallacies, research bias, or AI tools, make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

AI tools

Fallacies

Frequently asked questions about the slippery slope fallacy

Sources for this article

We strongly encourage students to use sources in their work. You can cite our article (APA Style) or take a deep dive into the articles below.

This Scribbr articleNikolopoulou, K. (2024, February 26). Slippery Slope Fallacy | Definition & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 1 April 2025, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/fallacy/the-slippery-slope-fallacy/

Jefferson, A. (2014). Slippery Slope Arguments. Philosophy Compass, 9(10), 672-680. https://doi.org/10.1111/phc3.12161