What Is Ecological Fallacy? | Definition & Example

An ecological fallacy is a logical error that occurs when the characteristics of a group are attributed to an individual. In other words, ecological fallacies assume what is true for a population is true for the individual members of that population.

Ecological fallacy can be problematic for any research study that uses group data to make inferences about individuals. It has implications in fields such as criminology, epidemiology, and economics.

What is ecological fallacy?

An ecological fallacy is an error in reasoning. Here, a fallacy is a deduction error, or a mistake we make when moving from the general to the specific. The word ecological is used to refer to a group or system, something that is larger than an individual.

Ecological fallacies occur when we try to draw conclusions about individuals based on data collected at the group level. For example, if a specific neighborhood has a high crime rate, one might assume that any resident living in that area is more likely to commit a crime. Stereotypical thinking like this assumes that groups are homogeneous, while in reality individuals may not necessarily share characteristics of the group they belong to.

When does an ecological fallacy occur?

An ecological fallacy occurs in research designs that use group-level or aggregate-level data to establish whether there is a potential association between two variables. These studies are called ecological studies, a type of observational study where at least one variable is measured at the group level. This can be, for instance, be at a district, state, or country level. Public health research often deals with these types of variables.

Per-capita sugar consumption is a variable measured at the group level, because it calculates the average sugar consumption for everyone in the country. Note that it does not mean that every person in the country ate exactly the same amount of sugar! An individual may consume less sugar or more sugar than the average. Similarly, the mortality rate is a group-level variable because it represents what is true for the country, not any individual person’s experience.

Crime rates in a certain area, per-capita sugar consumption, or mortality rates in a country are group-level data. With this data, we can draw conclusions about an area or a country, but not at the individual level. When we are moving from one unit of analysis to another, (i.e., from country level to individual level data), we are committing an ecological fallacy. If we want to draw conclusions about individuals, we need to collect data at an individual level.

What causes an ecological fallacy?

The root cause of ecological fallacies is the misinterpretation of statistical information. Researchers gather statistical data with the aim to generalize from the sample to the population, i.e., from the individual to the population, and not the other way around. When we collect group-level data, it’s a process similar to writing up a summary– certain details of information will be lost or hidden.

For example, in the previous study on prostate cancer, researchers found that there is a correlation between high sugar, meat consumption, and mortality from prostate cancer. Does this mean that we conclude that overindulging in sugar and steaks causes prostate cancer death? Can we use the results as dietary recommendations? The answer is no. While the study does provide insights into risk factors for prostate cancer, it does not establish causality. The data from this study is aggregated:what may apply on a population basis may not necessarily be observed on an individual basis.

Overall, a correlation tends to be larger when an association is assessed at the group level than when it is assessed at the individual level. As a result, when studies like these are analyzed at the individual level, the relationship often disappears.

In other words, while it may be true that countries with higher levels of sugar consumption have higher rates of prostate cancer deaths, this does not mean that individuals who eat a diet high in sugar are more likely to die from prostate cancer.

Ecological fallacy example

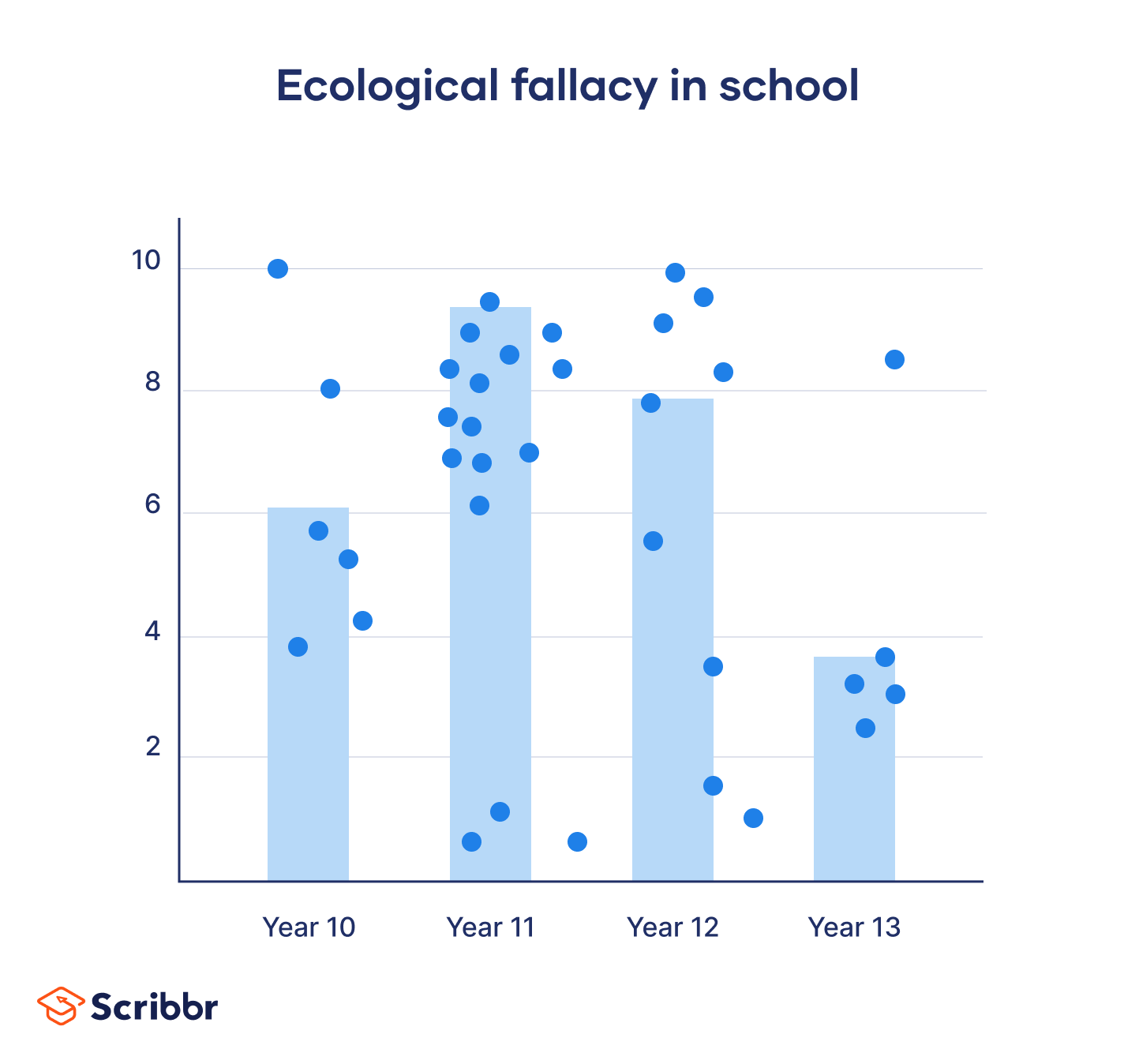

Ecological fallacies assume that individual members of a group have the average characteristics of the group at large.

After hearing this, one of the kids’ grandparents proudly looks at their grandchild, who is in Group A, and thinks to themselves “my grandchild must be a math whiz!” However, this is not necessarily true. Just because a student comes from the class with the highest average doesn’t tell us anything about their individual score. The student, for instance, could be the lowest math scorer in a class that otherwise consists of math geniuses.

Assuming that a randomly selected student from Group A would have a better score than a randomly selected student from Group B would be an ecological fallacy. The scores were an average and not a median, so we have no information about the distribution of the scores in the two groups. It might as well be that a randomly selected student from Group B scored higher than one from Group A.

How to avoid ecological fallacy?

We can avoid ecological fallacies in our own research designs or when interpreting research results from others by following the steps below:

- Clearly define the unit of analysis. Before collecting your data, consider who or what you are going to analyse. Is it individuals, groups, photos, or social interactions? For example, if you compare the students in two classrooms on test scores, the individual student is the unit. On the other hand, if you want to compare average classroom performance, the unit of analysis is the group, because the data you are analyzing refers to the group, not the individual.

- Be mindful of logical leaps. When drawing conclusions from your own research, reading research articles, or consuming data-driven news stories, take a minute to think: is the claim at the same level as the data? Or is the claim about individuals, while the data refers to a population? If so, this is a case of ecological fallacy.

- Keep in mind that results from group-level data can’t be applied to individuals. If you want to investigate individuals or subpopulations within a larger population, make sure that you obtain data from those individuals or subpopulations. This means that you need to follow a suitable sampling method, such as stratified sampling, if you are interested, for example, in specific subpopulations.

Frequently asked questions

Sources for this article

We strongly encourage students to use sources in their work. You can cite our article (APA Style) or take a deep dive into the articles below.

This Scribbr articleNikolopoulou, K. (2025, February 07). What Is Ecological Fallacy? | Definition & Example. Scribbr. Retrieved 24 December 2025, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/fallacy/the-ecological-fallacy/

Bell, K. (2020, June 27). ecological fallacy. Open Education Sociology Dictionary. https://sociologydictionary.org/ecological-fallacy/

Colli, J. L., & Colli, A. (2006). International comparisons of prostate cancer mortality rates with dietary practices and sunlight levels. Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations, 24(3), 184–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urolonc.2005.05.023