Within-Subjects Design | Explanation, Approaches, Examples

In experiments, a different independent variable treatment or manipulation is used in each condition to assess whether there is a cause-and-effect relationship with a dependent variable.

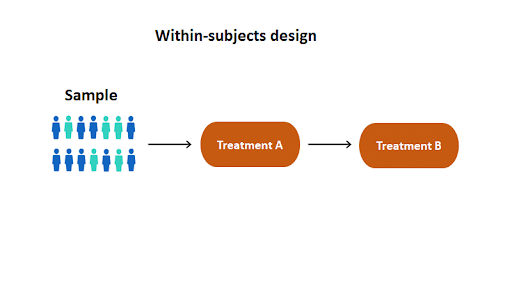

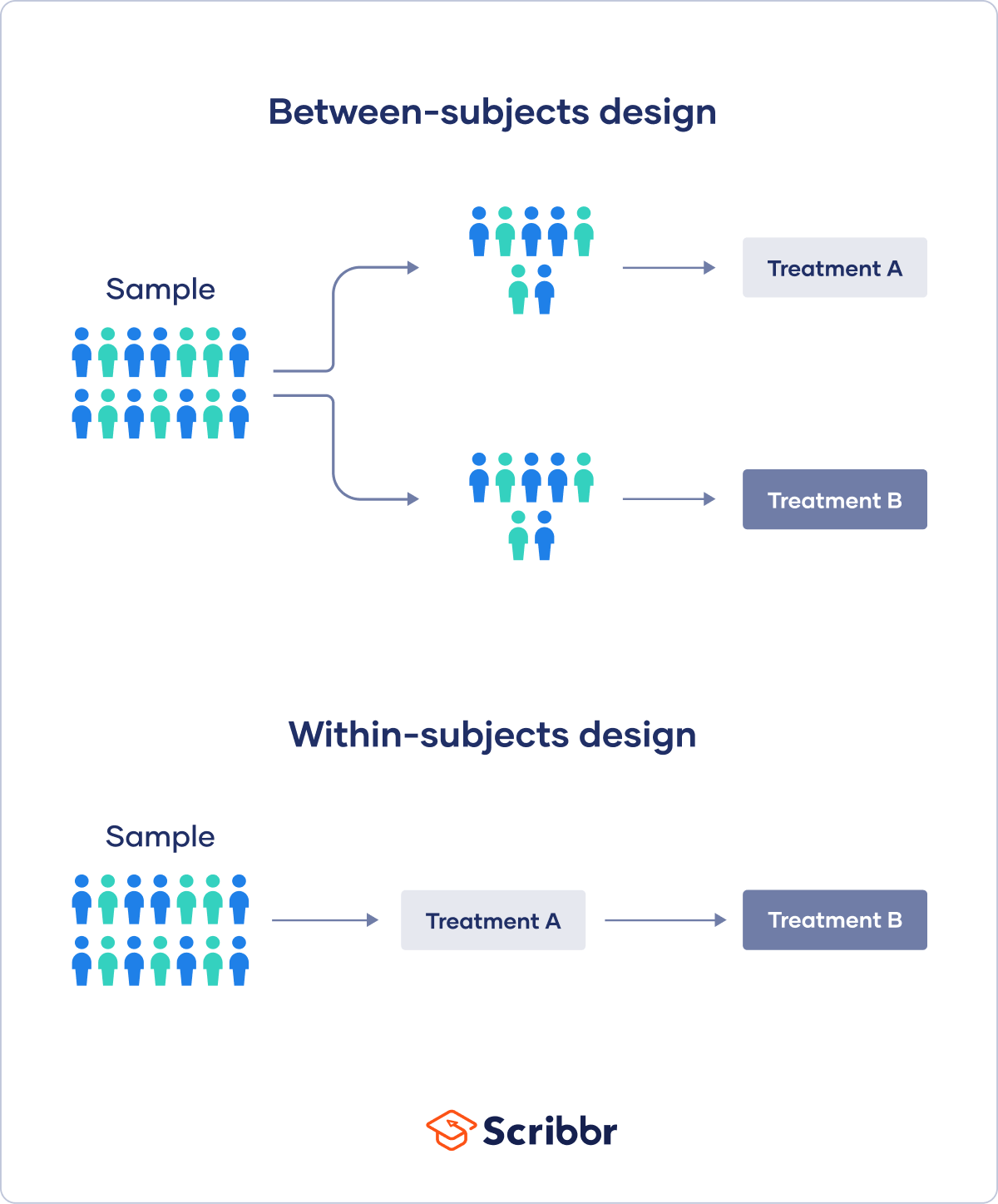

In a within-subjects design, or a within-groups design, all participants take part in every condition. It’s the opposite of a between-subjects design, where each participant experiences only one condition.

A within-subjects design is also called a dependent groups or repeated measures design because researchers compare related measures from the same participants between different conditions.

All longitudinal studies use within-subjects designs to assess changes within the same individuals over time.

Using a within-subjects design

In a within-subjects design, all participants in the sample are exposed to the same treatments. The goal is to measure changes over time or changes resulting from different treatments for outcomes such as attitudes, learning, or performance.

Other unrelated questions are also asked to make sure participants don’t guess the aim of the study. To test the effects of messaging styles on generosity, you compare the willingness to donate across conditions within subjects.

When comparing different treatments within subjects, you should randomise or counterbalance the order in which every condition is presented across the group of participants. This prevents the effects of earlier treatments from spilling over onto later ones.

Randomisation means using many different possible sequences for treatments, while counterbalancing means using a limited number of sequences across the group.

Counterbalancing is sometimes more convenient for researchers because an even portion of the sample undergoes each sequence of conditions selected by researchers. Each treatment ideally appears equally often in each position (e.g., third) of the sequence. This helps balance out the effects of treatment sequence on the outcomes.

To randomise treatment order, the order of the short stories is completely randomised between participants using a computer program. Every possible sequence can be presented to participants across the group, but in complete randomisation, you can’t control how often each sequence is used in the participant group.

In longitudinal studies, time is an independent variable. Because researchers can’t prevent the effects of time, longitudinal studies usually study correlations between time and other (dependent) variables.

To assess changes in perception, you compare differences in survey responses over time within subjects.

Within-subjects vs between-subjects design

The opposite of a within-subjects design is a between-subjects design, where each participant only experiences one condition, and different treatment groups are compared.

Between-subjects designs usually have a control group (e.g., no treatment) and an experimental group, or multiple groups that differ on a variable (e.g., gender, ethnicity, test score etc). Researchers compare the outcomes of different groups with each other.

In within-subjects designs, participants serve as their own control by providing baseline scores across different conditions.

The word ‘within’ means you’re comparing different conditions within the same group or individual, while the word ‘between’ means that you’re comparing different conditions between groups.

- a control group that takes a college course on campus,

- an experimental group that takes the same college course online.

You would administer the same test to all participants and compare test scores between the groups.

If you use a within-subjects design, everyone in your sample would take part in every condition:

- Half of the college course is administered on campus before a test.

- Half of the college course is given online before a comparable test.

You would randomise the order of the learning environment across the participants: some participants would first take the course on campus before switching to online learning, while the others would take the course online first before taking it in person. Then, you compare test scores within subjects between the two conditions.

In factorial designs, two or more independent variables are tested at the same time. Every level of one independent variable is combined with each level of every other independent variable to create different conditions.

In a mixed factorial design, one variable is altered between subjects and another is altered within subjects.

Some longitudinal studies can be experimental when they use a mixed design to study two or more independent variables. If you can directly manipulate one of the independent variables, and participant assignment to conditions, you’re using an experimental approach.

Each participant is randomly assigned to one of two groups:

- A control group that receives standard teaching methods,

- Another group that receives experimental teaching methods.

All participants are tested before, midway and after taking the course, and their scores are statistically tested for differences across time and between groups.

Pros and cons of a within-subjects design

-

Smaller sample

Within-subjects designs help you detect causal or correlational relationships between variables with relatively small samples. It’s easier to recruit a sample for a within-subjects design than a between-subjects design because you need fewer participants. Every participant provides repeated measures, making the study more cost effective.

-

Removes effects of individual differences between conditions

In a between-subjects design, different participants take part in each condition, so participant characteristics (e.g., intelligence or memory capacity) often vary between groups. This means it’s hard to say whether the outcomes are truly the result of the independent variable or individual differences between groups.

In contrast, there are no variations in individual differences between conditions in a within-subjects design because the same individuals participate in all conditions. Participant characteristics are controlled for.

-

Statistically powerful

A within-subjects design is more statistically powerful than a between-subjects design, because individual variation is removed. To achieve the same level of power, a between-subjects design often requires double the number of participants (or more) that a within-subjects design does.

-

Time-related effects

There are many time-related threats to internal validity that only apply to within-subjects design because it’s hard to control the effects of time on the outcomes of the study.

Some examples:

- History: an unrelated event (e.g., a lockdown) may influence the outcomes.

- Maturation: the natural physical or psychological changes (e.g., growth or aging) in the participants over time may cause the outcomes.

- Subject attrition: more participants drop out at every subsequent step of the study, leaving you with a potentially biased sample at the end because only participants with strong motivations stay in the study.

-

Carryover effects

Carryover effects are a broad category of internal validity threats that occur when an earlier treatment alters the outcomes of a later treatment.

Some examples:

- Practice effects (learning): familiarity with the study based on earlier conditions leads to better performance in later conditions.

- Order effects: the placement of a condition in a number of conditions changes the outcomes – for example, participants pay less attention in the last condition because of boredom and fatigue.

- Sequence effects: the interaction between conditions (based on their sequence) affects the outcomes; for instance, participants in an ad rating survey may compare later ads to earlier ones and base their decisions on the sequence of items.

Randomisation and counterbalancing of the order of conditions can help reduce carryover effects.

Frequently asked questions about within-subjects designs

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2022, April 11). Within-Subjects Design | Explanation, Approaches, Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 14 April 2025, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/within-subjects/